Who's afraid of the big bad wolf?

The myth lives on

The Wolf has featured as the bad character in fairytales for generations, but what is the real problem between humans and wolves? How come people are so vocal about this specific animal that they will go to such lengths, even violating EU environmental law and pay millions in fines just to hunt it? Wolves have had a complicated relationship with humans. For much of history they have been persecuted as competitors, and out of fear and ignorance. Yet favourable legislation in the European Union have recently allowed this species to re-establish in parts of the continent, in which it's considered critically endangered by IUCN.

|

| Gray Wolf. Photo: Gary Kramer - US fish and wildlife service |

The EU is closely monitoring Swedish wolf hunting

Karmenu Vella, the commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, has sent a reply to a letter from WWF, Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (SSNC), and the Swedish Carnivore Association (SCA). In the letter, Vella describe how “The Commission in July 2014 launched an infringement case against Sweden for failure to ensure appropriate access to justice, including to judicial review of administrative decisions, such as hunting decisions” and he goes on to write “Please be assured that the Commission is closely monitoring this issue and that it will not hesitate, if needed, to take all measures necessary to ensure that European Union environmental law is complied with in Sweden’s management of wolves”.

Wolf hunting in Sweden

Last december experts warned that Swedish wolf hunting may result in a fine of SEK 100 million if the issue goes to the European Court of Justice (SVD, 20 dec 2013). Thus, wolf hunting may become an expensive policy for taxpayers. That the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) granted licenced hunt for 16 wolfs last year lead to heavy criticism from the EU and an appeal by WWF, SCA and SSNC which resulted in a hunting ban awaiting the administrative court's sentence. The NGOs won the case but the sentence was appealed by SEPA and the Swedish Association for Hunters (SAH). The administrative court of appeal did however side with the three NGOs and sentenced the decision of 16 hunting licenses as unlawful. SEPAs motivation that hunting would lead to a decreased level of inbreeding in the Scandinavian wolf population lack sufficient evidence, according the the court. Even if the sentence would be appealed again it is unclear whether the Supreme Administrative Court would accept a trial.

Failure to comply with EU law

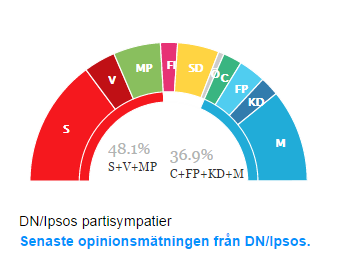

But now the government has opened up for hunting of more wolves, despite the administrative court of appeals decision that hunting 16 wolves was illegal. The general parliamentary motion period shows that many of the right-wing parties are positive to licensed wolf hunting. During 2014, 23 cases regarding hunting was brought up. But there is no general agreement on the topic (SVD, 2014) and SEPA has now transferred the decision-making to the county administrative boards in middle Sweden, which opens up for hunting licenses of up to 100 wolves according to some sources (SVD, 2014). Others claim the number to be around 44 wolves (Jönsson, 2014).

Facts about the Scandinavian wolf population

The wolf population in Sweden and Norway consist of a common Scandinavian population with spread over territorial boundaries. Yearly inventories are conducted over the entire Scandinavian peninsula winter time in respective country and also in Finland. During the winter 2013-2014 the Scandinavian wolf population has been estimated at 400 wolves in total (Viltskadecenter, 2014). Around 320 wolves are located only in Sweden, while 50 wolves are transboundary and 30 wolves live in Norway. In total 43 family groups have been documented. Finland registered 22 family groups in total, of which 14 live only in Finland and the rest are transboundary with Russia.The Scandinavian wolf population continues to increase. The population shows no significant change in growth rate during the last 16 years, with a yearly average growth rate of 15%. During this period the population has increased from 10 to 66 family groups. 40 wolf litters born during the spring 2013 were documented.

| Family groups in Sweden during the winter 2013-2014. Source: SLU (2014) |

The estimated average inbreeding coefficient of pups born in 2013 was 0.25. This is the next lowest number since 1998. During the winter 4 finnish-russian wolves were documented in Sweden. One male is located in Gävleborg and has produced four wolf litters during 2008,2009,2010, 2012. The female that was identified for the first time during the winter of 2010-2011, and was re-located by SEPA at several occasions, was also documented this year. The two wolves that were re-located during 2012-2013 from reindeer terrain in Norrbotten to the border between Örebro and Västra Götaland stayed and had a litter.

| Annual number of wolf litters confirmed in Norway (red ), cross-border Swedish-Norway (yellow), and Sweden (blue) during a 16-year-period, 1998-2013. Source: SLU |

During 2013-2014, 58 wolves were confirmed dead, 44 were found in Sweden. These numbers are included in the population estimate. In Sweden 26 (of 58) wolves were shot, 14 in self-defence and 12 in protective hunting. 9 died in traffic and another 9 died of unidentified causes.

Public opinion, nation wide

According to one public poll conducted by YouGov in 2012 (1009 respondents), commissioned by SSNC, the difference in opinions among city people and country side people is much lower than often claimed. The question posed was “The Swedish wolf population today consist of 260-330 individuals according to SEPA. Do you think the wolf population should be lowered through hunting?" The results showed that 59% answered No and 21% answered Yes across the country. Below is a chart showing the percentages divided by city size.

EU:s habitat directive

In order to ensure the survival of Europe’s most endangered and vulnerable species, EU governments adopted the Habitats Directive in 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. It sets the standard for nature conservation across the EU and enables all 27 Member States to work together within the same strong legislative framework in order to protect the most vulnerable species and habitat types across their entire natural range within the EU. Through the EU:s habitat directive wolves have returned to unlikely places in Europe. The return of breeding wolves to Germany during the last 14 years, and the recent arrival of dispersing wolves in Denmark is a striking example of how adaptable wolves are. And it brings optimism to carnivore conservation.The most important threats for wolves in Europe are: low acceptance among the rural communities, illegal killings, habitat fragmentation due to infrastructure development, and poor wildlife management structures.

.png)