Migration is a response to a changing environment

When soils become eroded, fresh water scarce, landscapes deforested, the air polluted and climate unstable, species either

adapt,

move or

go extinct. Because the climate is changing so rapidly most species have a hard time adapting to new conditions. Evolution would have to occur 10,000 times faster than it typically does in order for most species to adapt and avoid extinction. And so they move instead, along with the shifting climatic zones. According to a 2011

study, species are now moving to

higher elevations at a rate of 11.1 meters per decade and to

higher latitudes at an average of 16.9 kilometres per decade.

Life cycle events like mating, blooming and migrating that follow seasons are also changing. Mismatches in timing of births and food availability will inevitably lower population sizes of many species while pests and pathogens thrive due to warmer temperatures. Even if some species are able to migrate there are still many hinders (cities, high-ways etc.) on their way to territories where the competition for food will be tough. Highly specialised species and those who already live in the most northern regions might go extinct. For example, many Arctic species like the caribou, arctic fox and snowy owl are losing their habitat and the food they depend on at a rapid pace.

|

| From having been almost extinct in Sweden, some 15 years ago, the arctic fox may be on its way back, but only due to support feedings and a return of lemmings. Credit: TT |

Human mobility and Conflict

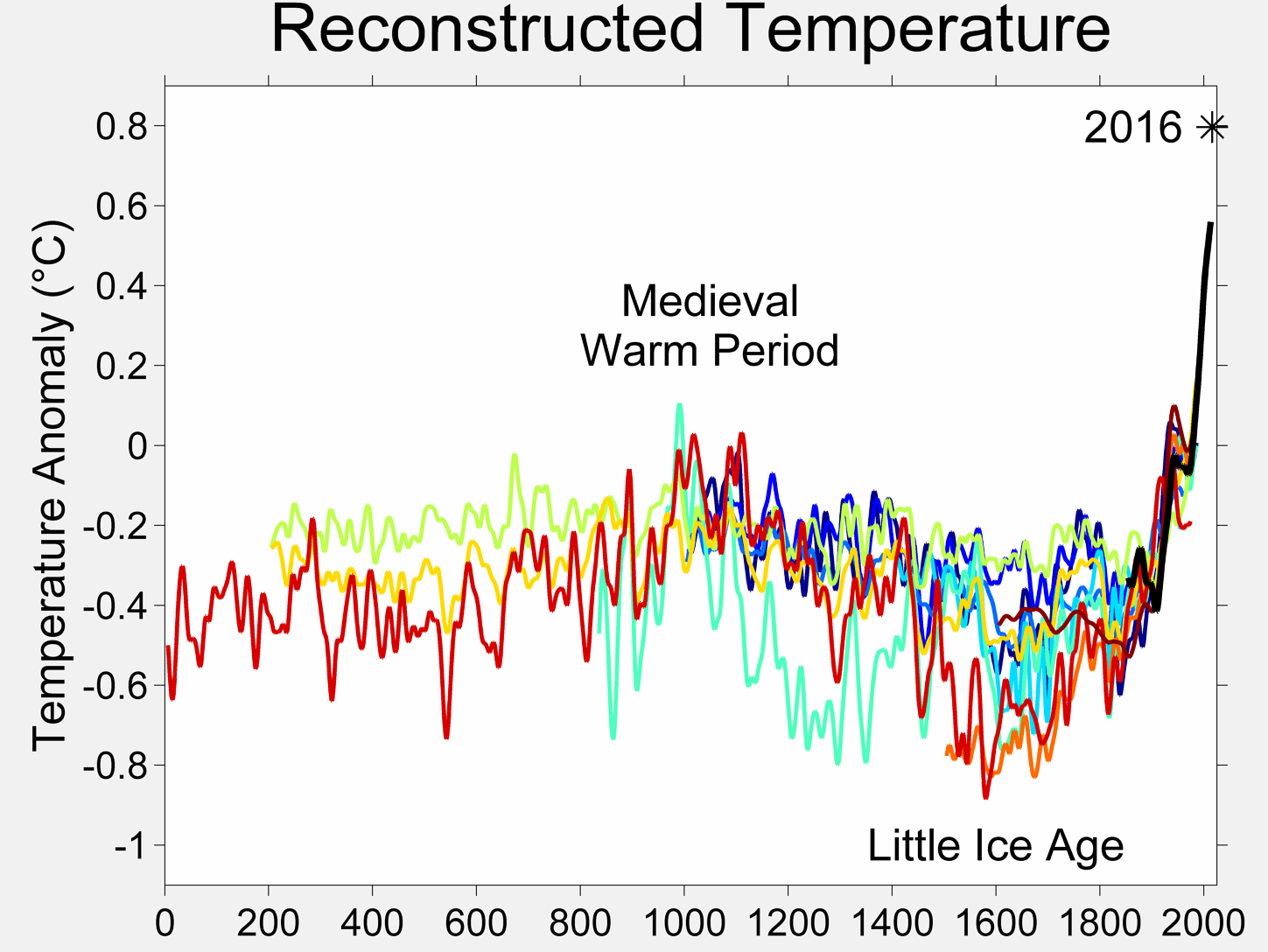

Human population mobility is not that different. For many of the poorest people of the world mobility is sometimes the only adaptive strategy available. Most sub Saharan African countries are finding it difficult to cope with existing climate stress, not to mention future climate change. Extreme weather events such as floods, droughts and storms have a direct impact on human migration patterns while long-term changes such as desertification and deforestation can lead to declining living standards that indirectly pushes people to move. Already at

+0.85°C warming, since pre-industrial times, we see a drastic increase in the number of displaced people.

Furthermore, when essential resources become increasingly scarce or costly tensions rise and conflict can break out. In Syria a devastating drought forced millions of farmers to abandon their fields in search of alternative livelihoods in the city. And when food prices spiked in 2008 and 2011, along with oil prices,

food riots and civil unrest broke out in a number of countries where people spend a large part of their income on food. Some of these conflicts have turned into full on wars which further reinforces migration.

People on the move

According to the

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) some 26.4 million people have been displaced by disasters (geophysical and weather related events) every year since 2008. The likelihood of being displaced by disaster today is 60% higher than it was in the early 1970s. The number of displaced people from natural disasters spiked during the strong El Niño years of 1997/98 which does not bode well for this winter and next year, with a similarly strong

El Niño now taking shape. Losses from natural disasters and conflict increasingly outpaces the adaptive capacity of a growing number of people around the globe who are forced to relocate permanently. According to

UNHCR,

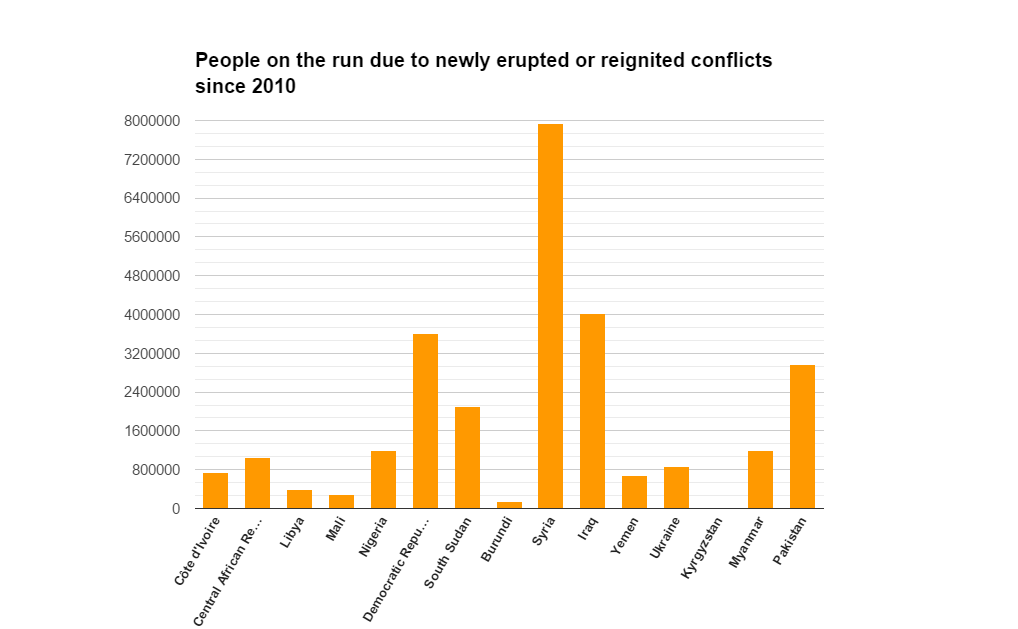

one in every 122 humans are now either a refugee, internally displaced or seeking asylum. The number of conflicts have increased during the last decade and 15 newly erupted or reignited conflicts have broken out since 2010.

|

Shows total people of concern (refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced, returnees, stateless,

and others of concern to UNHCR) in 15 countries as of 2014.

Based on UNHCR - Global Trends 2014: World At War |

Earth to humanity

Most people in Europe, and elsewhere, are currently focused on issues of immigration with endless political debates and moral outrage in mainstream media. People think that we are experiencing a political crisis but it's much worse than that.

Migration is only a symptom of the real underlying predicament - limits to growth in a finite world. As long as society tries to grow its population and economic activity we will continue to experience mounting social and ecological stresses, for example in form of: increasing inequality, disruptive climate change, mass migrations, hunger, epidemics etc. These pressures are warning signals that indicate overshoot, this is a

fact, and yet we refuse to talk about limiting population growth or downsizing our economy (i.e. lowering our energy per capita consumption).

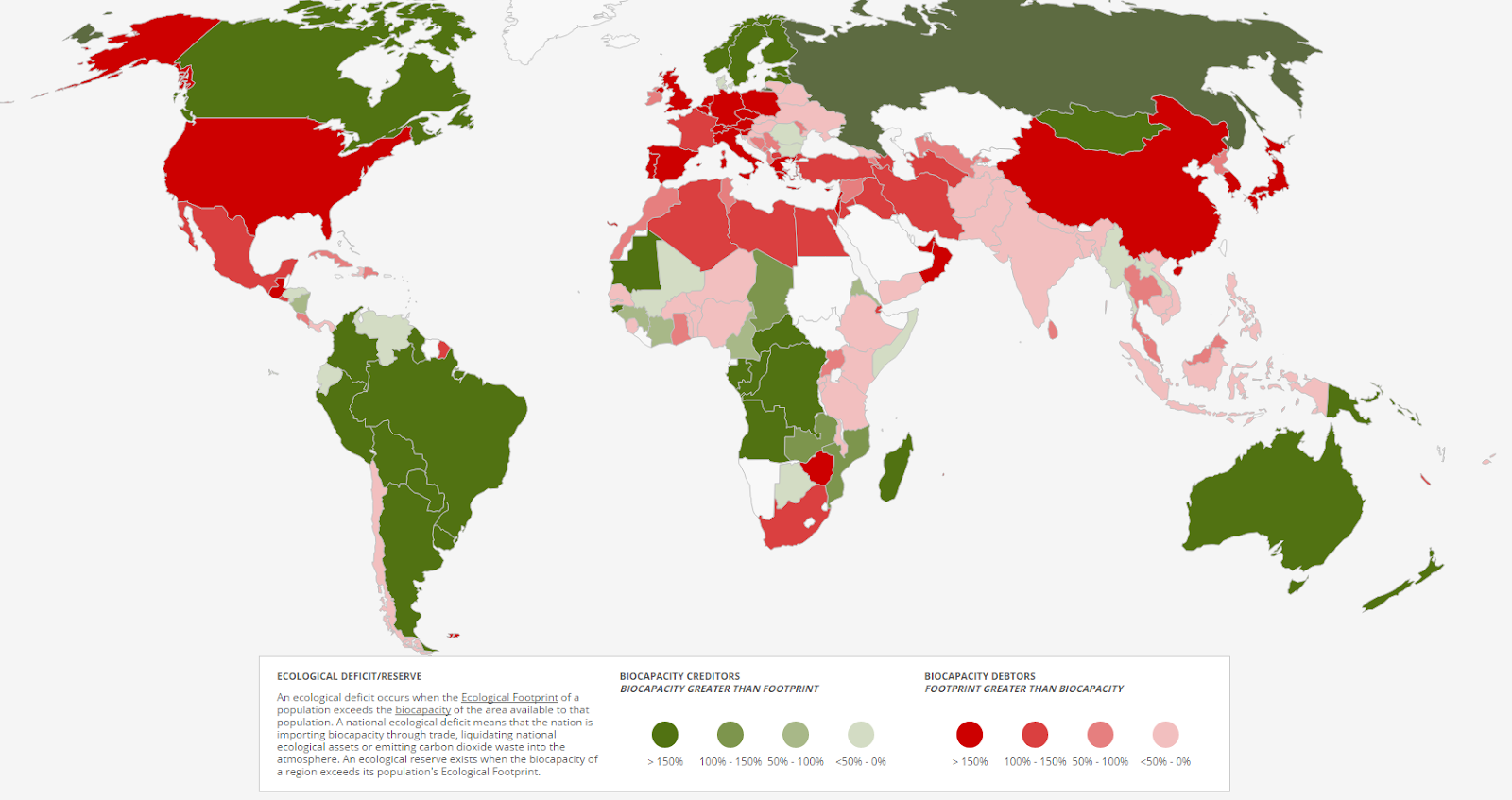

Irreversible change in carrying capacity means that a return to their homeland will be impossible for many refugees. Since ecological deficit is a global phenomenon, millions of ecorefugees will be seeking new locations. But very few places will have the biocapacity necessary to take them in without undermining their own ecological capital. Are there any lifeboats (nations) in suitable condition to accept ecorefugees on a long-term basis?

If we have a quick look at different country's biocapacity as measured by the ecological footprint network we can see that Canada, Australia, Scandinavia, Russia, Latin America and parts of southern Africa still have (in theory) the ecological capacity to host more people. While most countries located around the equator are in serious overshoot. However, not all countries are in overshoot for the same reasons, for example, the UK is a tiny country in landmass and have to rely on imports for pure survival while the US has plenty of land and could in theory support itself but not with current per capita over consumption.

|

| Green indicates ecological credit and red indicates ecological deficit. |

Accepting limits

Eventually, resource depletion and biophysical stresses will grow so large that the economy and population will have to contract. This view is based on

scientific evidence of population dynamics in a closed natural system. We can always hope for the best, but we better prepare for the worst, like any prudent risk manager would.

As most people probably have noticed by now, there is very little real wealth generation in today’s economy. Most of the economic activity these days consist of

wealth transfers, from the poor and the middle class to the financial elite. This is why we see such huge and widening gaps between rich and poor (

80 people own 50% of all global wealth). When the resource pie isn't growing anymore then one person's gains will always imply another ones loss, it's a zero-sum game.

Absent abundant, cheap energy (especially oil) the economy cannot grow and more people go broke and become excluded from the marketplace. Only the rich will be able to afford to keep on over consuming. Our society has tried to “paper over” this problem by piling up ever more debt (borrowing purchasing power from the future), but we have now reached a level when people cannot or are unwilling to take on more debt. And this is also why we see falling commodity prices, there just isn’t enough demand. Instead we have debt deflation. In time, depressed commodity prices could lead to falling supply which in turn could be devastating for food production and transportation. All the while pollution is growing and climate change becomes more severe.

Meanwhile, in Europe, social unrest and political extremism is on the rise once again. The so called “refugee crisis”, however, is neither temporary or political in nature. Ideologies like left or right-wing doesn’t matter anymore, only those who accept ecological limits and those who don't. We are simply too many people on a planet with a limited amount of natural resources and unstable climate. Now we have to share what’s left of the Earth’s riches, and people do not like it. Especially not the rich.

.png)